The First Week of Blended Learning: Two Perspectives

Context

Like most schools around the world, this primary school faces unprecedented challenges this fall precipitated by the new norms of COVID 19. After three and half months of complete online instruction, followed by a two-and-a-half-month summer break, students and teachers have been away from campus for almost six months. The first week of this school year was designated for online learning. During week two at this school site, teachers and students began learning in a completely novel form; blended or hybrid learning, in which some students learn face-to-face on the school site, while others learn from home either synchronously or asynchronously.

During this first week of hybrid learning, interviews were conducted with two members of staff, one a first-grade teacher, and the other a middle leader, serving in a coordinator/assistant principal role. These interviews provide a small glimpse, from two varying perspectives, into the challenges and opportunities of this new normal. The names of the interviewees have been changed.

The Ever-Changing Landscape

Four days prior to the start of school, Allison, previously a learning support teacher, received a phone call from the school’s leadership. In this conversation, Allison was informed that she would not be returning to her role as a learning support teacher but was needed to teach first grade. A teacher of 20 years, Allison is currently working on her master’s degree specializing in English as an Additional Language. She views her role as a support teacher as a crucial steppingstone for the next stage of her career. This last-minute change is difficult for her to accept. A few weeks prior to the new school year, in an effort to mediate the effects of budget cuts, the school withdrew the contracts of all new hires. While this measure secured employment for most, it has left some schools short staffed, and necessitated juggling teachers into new positions and roles, Allison being an example.

Early in our conversation, John, a school coordinator and leader, speaks about the challenges of an ever-changing landscape. The decision regarding new hires arrived with short notice and left leaders scrabbling to deal with its effects. Early in the second week, schools were notified that parents would now be able to choose the blended model or keep their children at home learning solely online. Again, leaders and teachers will have to reconsider their designs to accommodate this change. In reflection, John describes the need to be agile and pivot, to focus on your circle of influence and to accept what you cannot control.

Schedules and Learning Pods

In accordance with the staggered schedule at the school, instruction for the 1st graders in Allison’s class begins at 8:00 a.m. However, because some of her students have older siblings whose start times are earlier, some of Allison’s students arrive at school as early as 7:00 a.m. On the first day of school, three 1st graders arrive at Allison's class an hour early. These three students are unable to play with each other due to social distancing safety measures. They are not allowed to be outside, and they are not allowed to play with the classroom toys and materials. All these precautions are required by the Ministry of Education and Health and Safety’s requirements for face-to-face school. Allison gives her three students drawing materials to help occupy their one hour of waiting time. One of her students sits quietly crying; Allison is unable to console or distract him.

“So, blended learning…” John begins. “Over the summer, I’ve tried to do some research on blended learning. The problem is that nothing really applies. Everything I’ve read presents blended learning as a choice. There’s no choice in this situation.” John names his biggest challenge as the conflict between implementing structures and systems for the purpose of keeping children safe and the knowledge that these same systems are not in the best pedagogical or social/emotional interests of the child. He shares the staggered schedule the school has adopted and acknowledges that there are issues and adjustments need to be made.

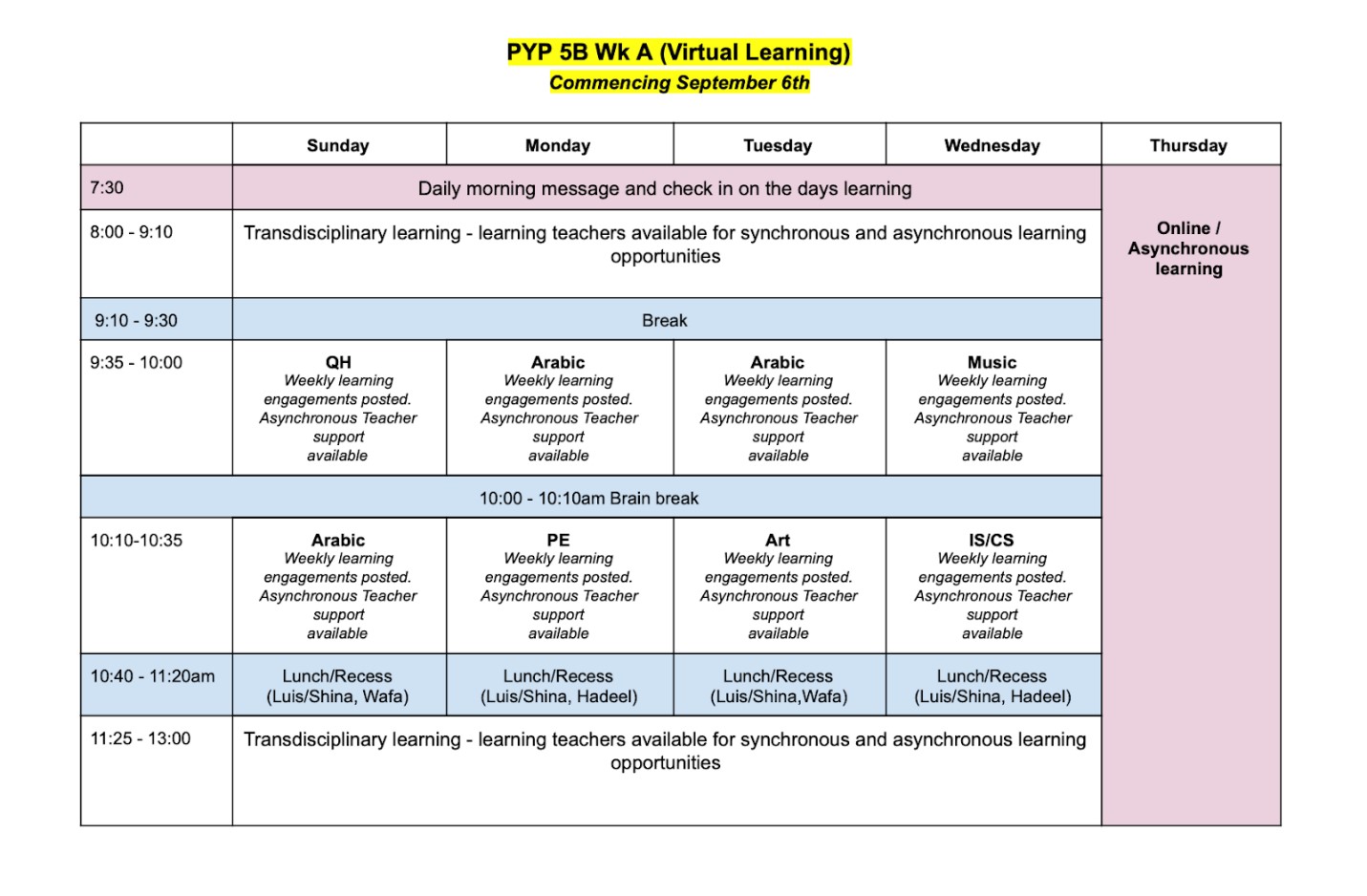

John shifts the conversation from schedules to the changes made to the classroom model. Students are on A/B schedules, alternating between one week of face-to-face and one week of online learning. However, during the week of face-t- face, classes are split into even smaller groups to maintain social distancing measures. Instead of one homeroom teacher supporting a class, there is now a group of teachers, including IAs and specialists, supporting a small group of learners. John describes this as a pod of learners circled by a group of teachers. He notes the challenges that this change has evoked for teachers. In this model, essentially everyone is now a generalist. Homeroom teachers now experience decreased control over their class/students and a required increase of communication and collaboration. Learners stay in their pods. Art, P.E. and Music classes are short online lessons even when students are face-to-face. This is the same for Arabic and National Programs teachers who are also being asked to support learning pods. This model will require a huge shift in the mindsets of teachers who have defined their careers up to this point within their role.

Reimagining Curriculum

In the first week of blended learning, Allison finds it challenging to think about the students learning online. She is in the classroom with her face-to-face students the entire workday. To complicate matters further, there are several issues with the school issued iPads. The iPads were distributed to parents, and the parents were asked to reset the passcodes. Teachers now do not have access to passcodes. The students in Allison’s class have forgotten the codes, and Allison can’t help them log on. This impacts specialist lessons, which are facilitated online even for face-to-face students. The iPads have yet to be updated and are missing the learning Apps, such as SeeSaw, Mathletics, and RazKids, required for online learning. Parents contact Allison for technical support. Allison questions how she will find time during her face-to-face week to meet the needs of online learners.

“We haven’t been able to focus on curriculum up to this point, but we are beginning to discuss it,” John shares. John’s body language and energy shifts, taking a noticeable up turn. When asked about how the PYP Framework might need to change in light of current circumstances, John clearly speaks of innovation within disruption. He and his team are exploring options, like shifting the curriculum from Units of Inquiry with Central Ideas, to essential competencies and developing ATLs. This thinking could lead to personalized learning paths, individual inquiries for students, and flexible grouping - maybe transcending grade levels. “There is opportunity in this,” declares John. “It’s exciting!”

Recommendations

Sprints

During our conversation, John specifically referred to Simon Breakspear’s work with Teaching Sprints. This model of quick cycles of data collection, trying something new, followed by review and reflection offers the opportunity to define and mobilize around a narrow focus of practice, seeking tiny changes. John refers to examining not only teaching practice, but also the systems and structures being devised during this time of disruption. As there is existing capacity within the school among members who have received the Breakspear training, and/or who have experience with data driven action cycles, the Sprint Model presents a promising opportunity for professional learning and growth. John also referred to the work of Stephen Covey and his concepts of the ‘circle of influence’ and the ‘circle of concern’. As “Begin with the End in Mind” is also a central theme in Convey’s work, this may be a key text to help frame the thinking around Sprints. Some questions for consideration are:

The Beginner’s Mind

“Beginner’s Mind,” although derived more from philosophical than pedagogical origins, may provide useful for sparking new ideas and igniting creativity. Patrick Buggy in his blog, Mindful Ambition, names “10 Exercises for Developing Beginner’s Mind.” These exercises could be adapted to use collaboratively when tackling problems that require a new perspective. The Right Questions Institute’s “Question Formulation Technique” similarly uses a structured protocol to collaboratively identify working questions to drive change.

Resources

Sprints :Click here

Cognitive Coaching :Click here

Stephen Covey : Click here

Beginner’s Mind :

Vanessa Miller

Lead Trainer

Education Development Institute